After weeks of media silence, with only whispers of “DAPL” or “Sacred Stone” or “Standing Rock” in social media and the alternative press, the Dakota Access Pipeline protest has hit the media with a loud bang. “Oil Pipeline Protest Turns Violent in North Dakota.” “Violence Erupts as Native Americans Resist Oil Pipeline.” “Violence Erupts At Oil Pipeline Protest.” “Clashes Between Guards And Native Americans In North Dakota Over Pipeline.” Sadly, the trite adage “if it bleeds, it leads” is in force, and what was known by mostly Native American and environmental activists has finally been headlined in the mainstream media. Very few of these stories, even those sympathetic to the concerns of the Sioux tribe, communicate the richness and complexity of what is now an encampment of thousands, but which began in April as the small Sacred Stone camp on the Standing Rock Reservation. Four members of Milwaukee’s Overpass Light Brigade decided to make the trip to Cannon Ball, North Dakota, to witness the protest and learn more about the people making a stand on the destruction site of the pipeline.

It is Friday night – our day one – and the stars spread low and drumbeats resonate throughout the sprawling tent and teepee city. Cars with WATER = LIFE bumper stickers, clay encrusted pickup trucks, busses full of people and supplies continue to stream into the camp, arcing down from the high road into the river valley that cradles us, and has cradled the local Sioux people for centuries. We hear laughter, a dog barks, the drums echo, someone hollers, a truck revs and there is singing, a night of singing. The Northern Lights streak into the sky, and we stand in awe, reflecting on the complexity of a very long day.

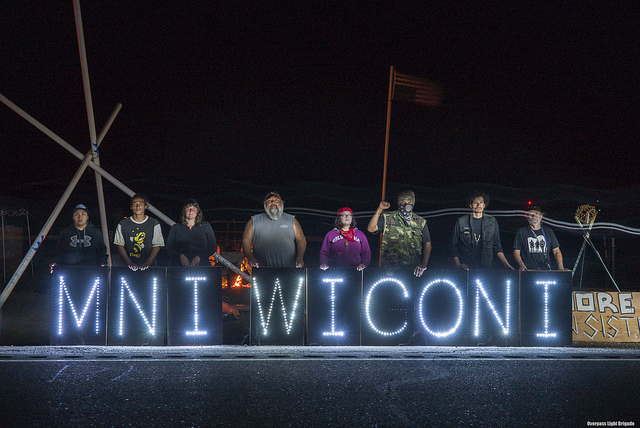

We arrived at Cannon Ball, North Dakota, on Friday afternoon amidst high wind advisories. We’d packed up a small set of letters for some messages, tents, snacks, and a few donations for the camp, excited to be going but uncertain about what would happen when we got there. It was transformative to slowly drive down the entrance road surrounded on both sides by a lineup of flags from tribal nations, so many people from around the country coming together in support of these protectors of water, the largest meeting of Native American tribes in 100 years or more.  A friend offered some advice about where to check in, how to make a brief proposal regarding our hoped-for Light Brigade actions, with whom to speak regarding permission, protocol, and respect: these subtle codes to navigate when we are guests in someone else’s house, outsiders with only brief and passing footprints. We were directed towards an older man sitting near the check-in tent and, after brief and somewhat awkward introductions, we tried to explain what we do and why we were there. “We hope to have community members help us hold portable lighted letters at night, spelling out messages…” we said. He sat thoughtfully and reflected, “What do the messages say?” and we responded, “They will say peaceful things, like MNI WICONI (which means “Water Is Life” in the Sioux language) and PROTECTORS, and ALL NATIONS…” We showed him a photo of a previous action about water on the shores of Lake Michigan, and he said, “Ah, yes. You can have the children help you.” He softened at this idea, and we agreed that this was an excellent plan. We hastily wrote an announcement, gave it to a different man with a mic – the voice of the camp – and he announced the Overpass Light Brigade action for that evening on the camp radio.

A friend offered some advice about where to check in, how to make a brief proposal regarding our hoped-for Light Brigade actions, with whom to speak regarding permission, protocol, and respect: these subtle codes to navigate when we are guests in someone else’s house, outsiders with only brief and passing footprints. We were directed towards an older man sitting near the check-in tent and, after brief and somewhat awkward introductions, we tried to explain what we do and why we were there. “We hope to have community members help us hold portable lighted letters at night, spelling out messages…” we said. He sat thoughtfully and reflected, “What do the messages say?” and we responded, “They will say peaceful things, like MNI WICONI (which means “Water Is Life” in the Sioux language) and PROTECTORS, and ALL NATIONS…” We showed him a photo of a previous action about water on the shores of Lake Michigan, and he said, “Ah, yes. You can have the children help you.” He softened at this idea, and we agreed that this was an excellent plan. We hastily wrote an announcement, gave it to a different man with a mic – the voice of the camp – and he announced the Overpass Light Brigade action for that evening on the camp radio.

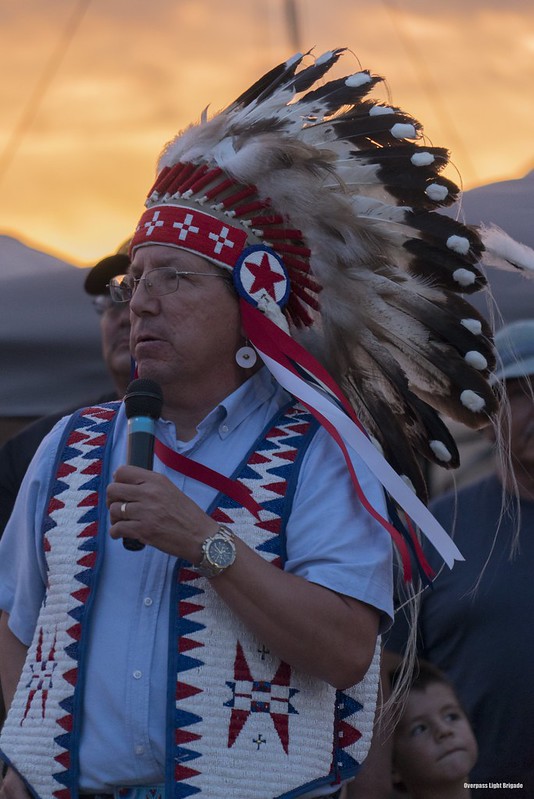

We set up camp in the wild wind, trying to find a little shelter near a willow break, struggling against the 40 mph gusts and gritty dust. People continued to arrive in a constant stream. Kids on horses, bareback, trotted by, heading up to the check-in area, or down to the river. Different areas of the encampment had subtly different moods and inhabitants. Many families and clans set up their own communities in the fairly unstructured campground. Formal corrals and informal stumps with ropes were set up here and there for horses. A giant truck hauling round bales visited each corral to be sure the horses were fed. As darkness fell, we worked our way back up to the main area, to the Avenue of Nations. Lawrence O’Donnell from MSNBC and Amy Goodman from Democracy Now! were both being introduced in the circle near the Check-In tent, and both spoke very briefly about their commitment to being vehicles for the indigenous communities to help tell *their* stories. We couldn’t know then that the next day, Amy Goodman and her crew would be instrumental in getting important footage of the attack at the construction site, when guard dogs were released on peaceful protestors. As they were being honored, a Nakota delegation arrived in ceremonial regalia, staffs, eagle feather headdresses, beautiful shirts and pants. The microphone was handed around to each of the delegation, and there was a welcoming ceremony: our first of many, as the following day greeted many more tribal delegations from across the country.

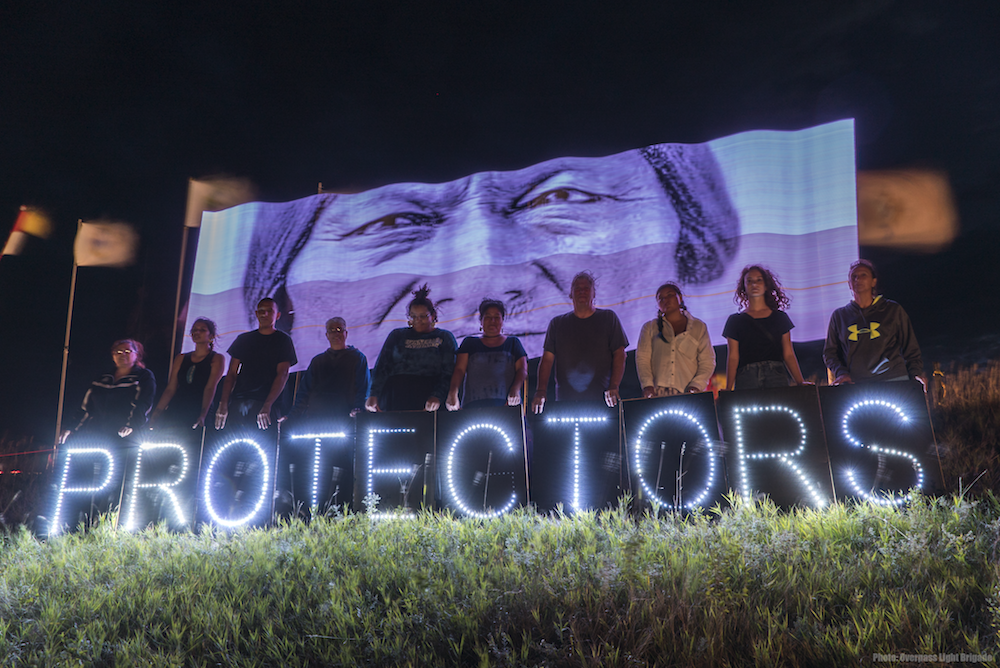

As the welcoming ceremony ended, we pulled out the letters, lighting them and leaning them against the van for all to see. OLB is so much easier to understand by doing and seeing than by explaining. We gathered some wonderful volunteers, and held ALL NATIONS and then PROTECTORS with the tribal flags blowing overhead, and the darkening stormy sky in the background.

Day Two arrived with long shadows from the eastern sun. A cool morning soon heated up with a blistering sun and strong wind. That morning, the Tribes of the Colorado River arrived for another welcoming ceremony. Women from west coast tribes walked down the long dusty camp road to the river, then walked back to the main camp for their welcoming ceremony. The diversity was rich and the pride palpable. A yellow helicopter circled overhead, thud-thud-thud, and we heard a number of jokes about surveillance and being on Homeland Security data files.

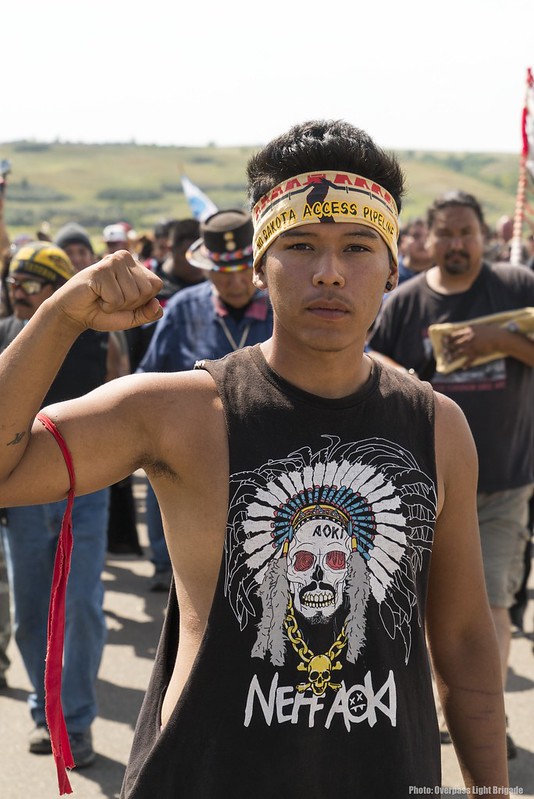

We drove the two miles to the construction site up Highway 1806, the “Native American Scenic Byway.” The digging and land scraping were on hiatus by judicial order, or should have been, awaiting a judgment on whether the Standing Rock community had adequate opportunity for public input. This ruling will be very soon, before September 9. Since filing that motion, the Standing Rock Sioux have filed a temporary restraining order to stop the desecration of culturally significant artifacts on the pipeline site. There is already $3.8 billion invested in this project, with many multinational banks involved in the financing. The forces against the river are strong, powerful, and interconnected. This encampment is the cutting edge of a surprising resistance. As we returned to camp for the Horsemanship event, we met a march on its way to the pipeline site, different tribal elders at the front, being assisted as they walked in the hot, beating sun. We didn’t know at the time, but this march formed the nexus of the protectors who stopped the surprise bulldozing, despite the order to halt construction, that happened later in the day.

We gathered with others at the impromptu racetrack, under the scant shade of small, scrubby willows, and waited for the riders to appear. They arrived on an array of beautiful horses: chestnuts, grullas, dapple grays, showy paints. Small groups, sorted by age and experience, took to the uneven track, taking off like bullets at the starting line, rounding the far curve and hurtling back towards us. One girl fell from bareback racing, and might have been seriously hurt, so we all clapped and cheered when she rose off the hard ground. After the horse races was a Boot Race for the little kids, who piled up their footwear on the track, ran to the pile barefoot, put on their shoes, and stumbled back to the finish line with laces untied.

While families were enjoying these joyful, uplifting, inclusive events, a couple hundred water protectors who had earlier marched up the hot highway found the bulldozers at work, recklessly scraping through sacred burial sites and artifacts in the pipeline’s route, in deliberate defiance of the order to stop construction. The Protectors rushed to stop the desecration, and were met by private security force who unleashed guard dogs and pepper spray at the crowd. Dogs lunged and bit, injuring men, women, children, horses.

Back at Sacred Stone camp, Indigenous Environmental Network activist and Native American organizer, Dallas Goldtooth announced the need for upcoming civil disobedience training that the organizers hoped everyone would engage, reiterating the importance of keeping the movement peaceful. They set up a “scout camp” at the construction site, so that the Water Protectors, who “stood their ground and peacefully made the machines turn around“ will have a constant view of what the corporation is doing on the land. All volunteers were requested to go through security clearance and training. Our original hope to find horsemen willing to hold a lighted message did not come to pass. The events up at the construction site changed the tenor of the evening, even as more people flowed into the camp, unaware of the violence of the afternoon. Instead, we headed up to the newly established Scout Camp with two messages, after discussing our desire with Dallas Goldtooth, who felt it was a good idea as long as we got the permissions from the people doing guard duty. We pulled up in the dark of dark night, edged off the raised highway. It is awkward to approach strangers in the dark along the side of an empty, remote highway. In the darkness we said hello, that we had a request and wanted to talk. We told them who we were, the Light Brigade, and thankfully, one young activist was aware of our work. That made everything so much easier! Soon we were passing out the message, and thanking them for their courage and dedication, and allowing us to be a part of their night, a small part of the story.

On the way out, about 30 miles north, we drove through the roadblock barricades (tents with concrete barriers buttressed with sandbags) set up by law enforcement to prevent people from accessing the protest site from Bismarck. A uniformed man waved us through with his red lighted baton. You can leave, but you can’t enter. It was an absurd and provocative show of force and exercise of control.

It is difficult to process all of this. The experience was so rich and a part of that richness was our own discomfort. We had no standing in the community, few friends, and an overwhelming sense of the awkwardness (at best) inherent in our inviting indigenous people to participate in our project staged in their space. While this struggle is ostensibly a fight over a pipeline with its potential to ruin a river, it is much more than that. We outsiders need to understand what is going on, what kind of movement is percolating, flowing, growing. We are deeply grateful that we had the opportunity and resources to make this journey and experience this unprecedented coming together, and hope that we were able to bring a little bit of light to the magical nights.